Background

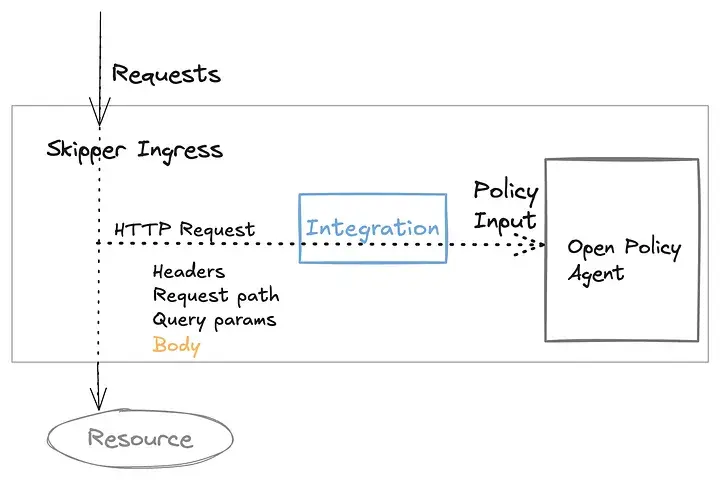

This learning comes from a project aimed at providing Externalized Authorization as a Service (AaaS), integrated directly into the platform. The solution leverages Open Policy Agent (OPA) as the Policy Decision Point (PDP), with policy enforcement handled by Skipper — an open-source ingress controller and reverse proxy. Skipper integrates with OPA to serve as the Policy Enforcement Point (PEP). For a detailed overview, refer to this Zalando Engineering blog.

As an ingress controller, Skipper is designed to introduce minimal overhead to requests. Given the large number of deployed instances, any inefficiency in resource allocation can quickly scale into significant costs. Similarly, even a delay of just a few milliseconds per request becomes expensive when multiplied across thousands of requests flowing through Skipper. Now should we save the goat or the cabbages?

Optimization

Conditional HTTP body parsing optimization

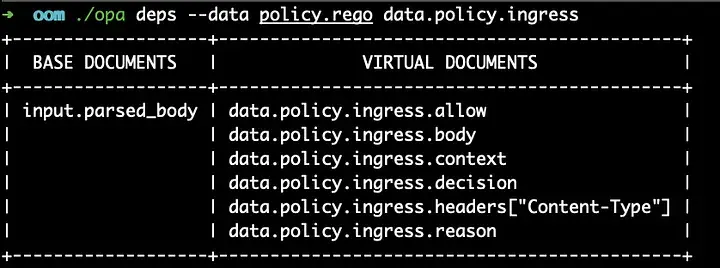

When Skipper receives an HTTP request, it transforms the request into a format compatible with OPA. To optimize memory usage, parsing of the HTTP body is performed conditionally, avoiding unnecessary overhead. Parsing is triggered only if the active policy in OPA explicitly depends on the HTTP body. OPA provided a very straightforward call to deduce this with,

dependencies.Base(opa.Compiler(), opa.EnvoyPluginConfig().ParsedQuery)

Dependency base calculation flow

So if the function sees parsed_body is a base document of the policies, HTTP body will be parsed. For simple policies this was working smooth and fine, but things started to get more interesting and challenging as the policies get complex.

How it backfired

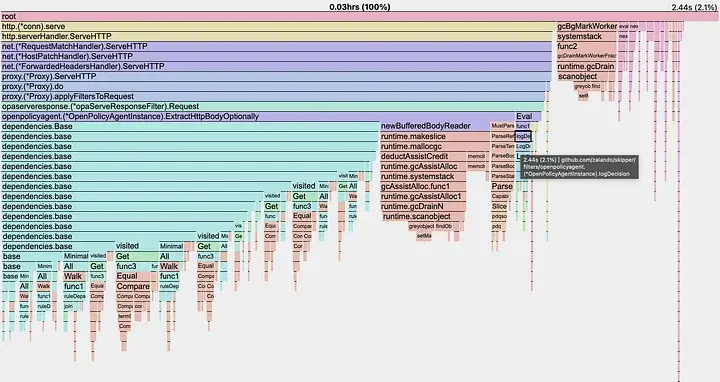

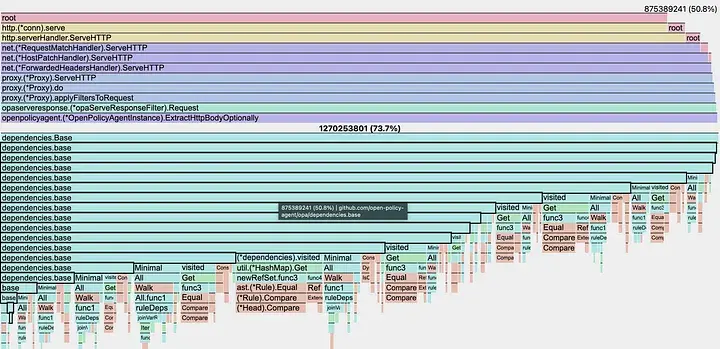

Dependency base calculations should not be underestimated, as they involve costly graph traversal, particularly with recursive function calls. The complexity and overhead of recursively processing dependencies escalated as the policy grew. Thanks to the OPA community, the base function was optimized (as shown here), but since it remained recursive, the improvement only provided limited relief. The result was that, before the parsed body could fill the memory, it was already being consumed by the dependency calculation objects, and the calculation added to the CPU load.

CPU profile

CPU profile showing dependency calculation overhead

Memory alloc object profile

Memory alloc object profile

Trade offs

At this point it was clear the optimization has backfired and we got rid of it with few guards in place.

In some cases, policies were updated frequently. However, in most use cases, whether the HTTP body is used in the policy decision is not a per-request decision, but rather a system attribute that can be set when policy enforcement is enabled. This approach eliminates the need for dependency base calculations entirely.

We could also calculate the dependency.base just after each policy bundle loading to OPA. This reduces the calculation to per policy update than to per request which is better. Still if the policies get updated frequently (with near real time access data etc.), the issue will still arise.

As of now, we opted to option 1 and entirely got rid of the dependency base calculation (The implementation with before/after CPU and memory profiles and benchmark test can be found here). This means body of the each request will be parsed. As a guard we have a configurable max limit for body size to be parsed. This approach allows for a more accurate estimation of how many requests a single Skipper instance can handle, taking into account the available memory, and enables scaling based on anticipated traffic with a safer margin.

The Result

🎉🎉 🎉 After removing the optimization, we only needed 11 instances of Skipper for the same RPS it was serving with 23 instances, gaining a more than 50% save.

Key Takeaway

As context evolves or complexities grow, optimizations may need to be reassessed. Without continuous benchmarking close to real-world scenarios, we might not notice issues until they become significant!